I spent weeks and hundreds of dollars trying to hire people to help me with my videos and content. It didn't work out. So I did what any engineer would do: I built agents instead.

What started as a frustration became one of the more interesting engineering exercises I've done recently -- not because the agents themselves are complicated, but because the decisions about how to structure them taught me something about orchestration that I think matters well beyond content creation.

Here's what I learned building a small AI team, and why the thinking behind it matters more than the tools.

Agents Are More Than Just Prompts

Let's start with something people overcomplicate -- and then oversimplify in the other direction: what an agent actually is.

An agent isn't just a prompt. It's a prompt combined with a defined scope, a set of permissions, access to specific tools, and potentially a selected model. In Claude Code, an agent is a markdown file -- an agent.md -- that describes what the agent does, how it should behave, what context it needs, what tools it can use, and how it interacts with you. The permissions matter: can it write files? Can it run shell commands? Can it call other agents or skills? The model selection matters too: do you need the most capable model for this task, or is a faster, cheaper one sufficient?

But even with all that, the interesting part isn't the mechanism. It's the design decisions. What goes into that prompt? How much context does it need? What scope should it own? Where do you draw the boundary between one agent and another? What tools does it really need access to?

These are system design questions dressed up in natural language. And getting them right matters the same way getting your service boundaries right matters in a distributed system.

The Agent vs Skill Decision (And Why It's a Real Architecture Choice)

Here's where I had to actually think. Claude Code gives you two constructs: agents and skills. They look almost identical on the surface -- both are markdown files with instructions. Both are prompts. But they have a critical structural difference that maps to a real engineering concept.

A skill shares your main context window. It's like a function call within your current process. You invoke it, it does its thing using the same memory and state you're already working in, and returns. Think of transcribing audio or generating an image -- bounded, stateless tasks that don't need to know about your broader project goals.

An agent gets its own context window. It's like spinning up a separate process (or hiring a separate person). You delegate work to it, it operates with its own understanding of the task, and it can run through multiple iterations independently. It can look at previous work, reference your content strategy, iterate on drafts with you.

This distinction sounds academic until you're actually building. Here's why it mattered.

I needed to transcribe videos and generate images. Both are one-shot operations. Give it a file, get output back. No iteration needed, no memory of previous runs, no need to understand my content strategy or brand voice. These became skills -- transcribe and imagen. Small, focused, stateless.

But writing a blog post? That needs to understand my voice, my content strategy, previous posts I've written, how I structure arguments. It needs to iterate with me -- propose an outline, get feedback, draft sections, revise. It needs to know where files should go in my project structure. That's an agent -- blogen -- with its own context, its own working memory, its own ability to run through a multi-step process.

Same for LinkedIn content. The linkedingen agent needs to understand LinkedIn-specific formats, my audience on that platform, the right post length, what hooks work. Different context from the blog agent, even though both might draw from the same source transcript.

The mental model that helped me: skills are pure functions; agents are stateful services. Skills transform input to output. Agents hold context and iterate toward a goal. If you wouldn't spin up a separate microservice for it, it's probably a skill. If you would, it's probably an agent.

What Goes Into an Agent Prompt (The Interesting Engineering)

Building these agents forced me to think carefully about something most engineers skip: codifying tacit knowledge.

When I sat down to write blogen, I couldn't just say "write blog posts." I had to articulate:

- Voice: What does my writing actually sound like? Not "professional and engaging" (useless). Specific patterns -- conversational, uses first person, mixes short punchy sentences with longer analytical ones, shares failures openly, avoids corporate jargon.

- Content strategy: What themes do I keep coming back to? Iron Man suits, the two-expert problem, building in public. The agent needs to know these so it can weave them in naturally.

- File organization: Where does a draft go? Where do assets live? What naming conventions matter? This is the kind of thing you'd explain to a new hire on day one.

- Iterative process: Don't write the whole post at once. Propose an outline. Wait for my feedback. Draft section by section. Ask specific questions. This is how I actually work with a human collaborator.

That last point is the one most people miss. The instinct is to tell the agent "write me a blog post" and expect a finished product. That's the vending machine model. What actually works is the collaborator model -- you encode the process, not just the goal.

This is exactly what you'd do onboarding a new team member. You wouldn't say "go build the feature." You'd say "here's how we work: we start with a design doc, we review it together, we break it into tasks, we iterate." The agent prompt is your onboarding doc for an AI teammate.

And here's what surprised me: writing these prompts made me better at articulating my own process. I discovered patterns in my content workflow I'd never made explicit. The act of teaching the agent taught me something about how I work.

One more thing worth mentioning: you don't have to build everything from scratch. There's a community site called skillmp.com where people share pre-built skills you can download -- image generation, code review, all kinds of things. Many are just a prompt and maybe a Python file. I tried a few, ended up building my own for tighter integration with my content structure, but it's a great starting point if you want to get moving fast.

Orchestration: Start Manual, Productionize Later

Everyone hears "orchestration" and thinks frameworks. LangChain. CrewAI. Those can absolutely work -- and for production systems, you'll probably want something like them eventually. But I didn't start there, and I think that's the right approach.

My orchestration layer is... me. Talking to Claude Code.

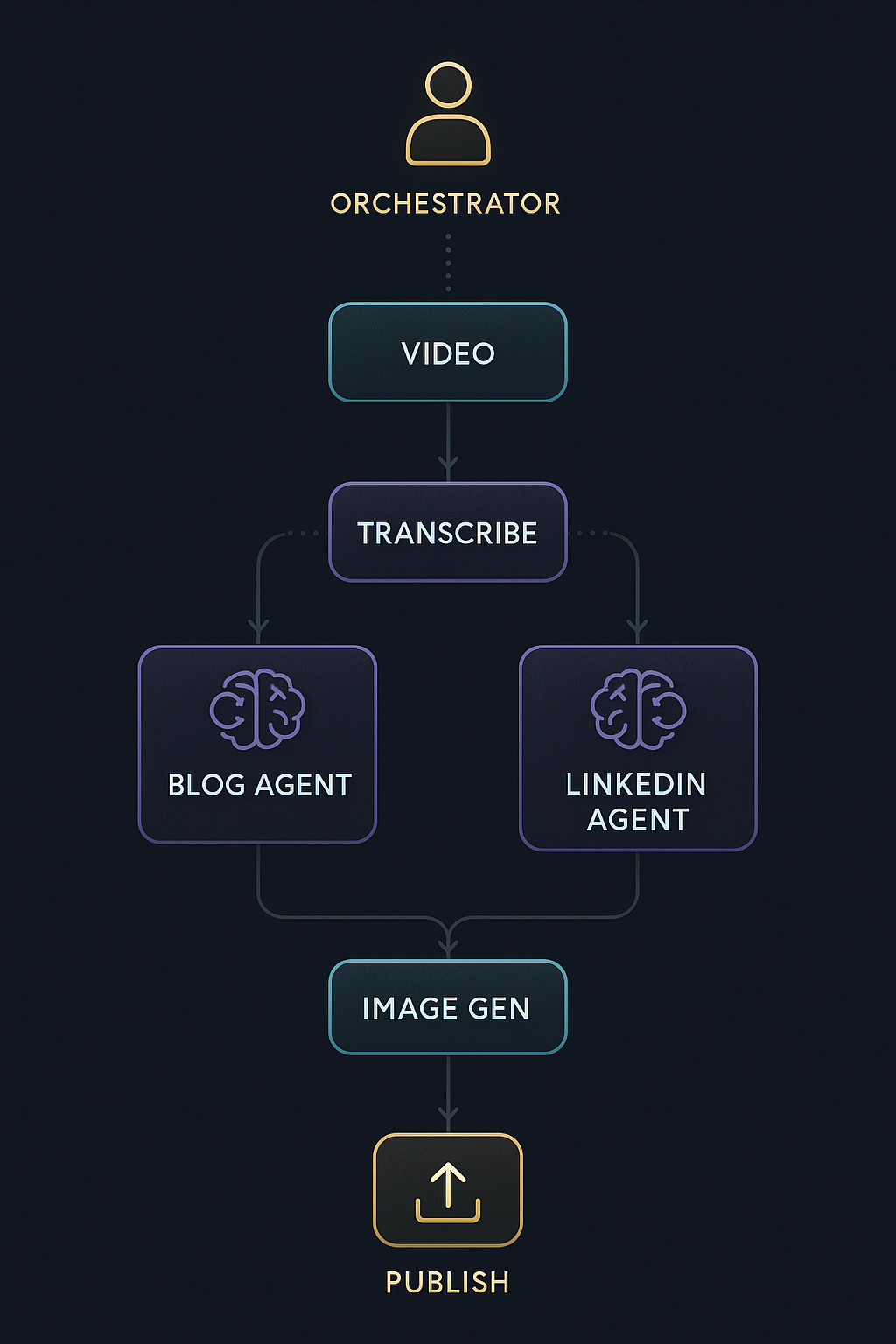

I am the orchestrator. I look at a video I've recorded and decide: first, transcribe it (invoke the transcribe skill). Then, read the transcript and decide what content to create. Invoke blogen for a blog post. Iterate with it. When the draft is solid, invoke linkedingen to create a LinkedIn post from the same source material. Need images? Invoke the imagen skill.

The agents and skills don't talk to each other directly. I'm the router. I make the decisions about what runs when, what output feeds into what input, when to iterate vs when to move on.

This is a deliberate choice, not a limitation. And it maps to something I believe deeply about where we are with AI right now: this is the Iron Man suit era, not the autonomous agent era. I'm in the suit. I'm making every decision. The agents amplify my capability -- they handle the heavy lifting of drafting, generating, formatting -- but I'm steering.

Here's why starting manual matters: it lets you test and iterate on the flow before you lock it in. You can even use Claude Code to run orchestration in the background -- kick off multiple agents in parallel, let them produce drafts while you review other outputs. Once you've iterated enough to understand the workflow deeply -- which decisions are routine, which need human judgment, where the handoffs happen -- then you move to a production-ready framework like LangChain or CrewAI.

This is how good engineering works in any domain. You don't start with the production architecture. You start with the prototype, you learn what actually matters, and then you productionize what works. Trying to build the production orchestration pipeline on day one is the same mistake as building a microservices architecture for a greenfield project. Get the flow right first.

Where Orchestration Breaks Down (Honestly)

Orchestrating agents through Claude Code is not perfect. Let me be specific about what goes wrong, because these are the friction points that matter if you're going to try this.

Agents get confused about which tools to use. At one point, the blog agent was supposed to invoke the image generation skill. Instead, it just called the underlying Python script directly, bypassing the skill entirely. Some level of orchestration was still happening, but not through the path I'd designed. The LLM lost track of the abstraction layer. This happens more than you'd like.

Agents forget to call each other. You set up a workflow where agent A should hand off to agent B, and instead agent A just tries to do everything itself. Or it calls a tool directly instead of going through the agent you built for that purpose. The orchestration isn't reliable in the way a programmatic pipeline would be. It works well enough -- but "well enough" means you need to watch it.

New models change behavior. This one caught me off guard. When a new model version rolls out, your carefully tuned agent.md might behave differently. The agent that used to reliably ask clarifying questions before drafting might suddenly just start writing. The one that used to use the image generation skill might start hallucinating its own image descriptions instead. Your agent definitions must be iterative. They're not write-once artifacts. They need maintenance as the underlying models evolve -- just like any other interface that depends on an external service.

The LLM always wants to over-build. When I asked Claude to create the Webflow upload tool, it offered three options: a simple script, a full automation suite, and an enterprise system. I picked the simple script. The instinct to say "yes, build the enterprise version" is strong -- especially when the AI can do it in minutes. But this is the same trap as over-engineering any system. Build the simplest thing that works. You can always extend later.

Permissions are wonky. In theory, you can scope what each agent is allowed to do -- file access, shell commands, tool usage. In practice, locking permissions down to specific folders or operations is harder than it should be. An agent that should only write to content/blog/ might try to write elsewhere, and the permission system doesn't give you the fine-grained folder-level control you'd want. It's one of the weaker points of using Claude Code for agent orchestration right now. You end up relying on trust and verification more than enforcement.

Visual content is a mixed bag. AI image generation has gotten genuinely impressive -- it can produce really cool generated images that work great as hero images and illustrations. But when it comes to diagrams, flowcharts, and technical visuals, it struggles. Mermaid diagrams look super basic. Getting precise, structured visuals from AI models is still a battle. It's something I'm actively working on figuring out how to improve.

These aren't deal-breakers. The system works. But it works the way an early-stage product works -- you need to stay close to it, debug issues as they come up, and iterate on your agent definitions regularly.

The Results (Concrete)

Two days of building and iterating got me:

- A transcription skill that handles video-to-text reliably

- An image generation skill using my own API keys and content preferences

- A blog generation agent that writes in my voice and follows my content structure

- A LinkedIn generation agent tailored for that platform

- A Webflow upload tool for publishing

- A first blog post and LinkedIn post that got real traction -- 28 reactions, 12 comments, almost 9,000 impressions on LinkedIn, and inbound requests

Two days. The hiring process that preceded this took weeks and produced nothing usable.

But the real result isn't the time savings. It's the system. I now have a repeatable, improvable content workflow. Each agent gets better as I refine its prompt. Each run teaches me what to adjust. The system compounds.

What This Means Beyond Content

I built this for content creation, but the pattern applies to any engineering workflow where you have:

- Bounded, repeatable tasks that don't need much context (make them skills)

- Complex, iterative tasks that need domain knowledge and human collaboration (make them agents)

- Decision points that require human judgment about what to do next (keep those with you -- for now)

This is how AI integrates into real engineering workflows. Not as a magic box that does everything. Not as a replacement for thinking. As a set of specialized, well-scoped AI teammates that you orchestrate -- with yourself as the thinking layer.

The orchestration frameworks will get better. The agents will get smarter. The context windows will get bigger. Eventually, some of those decision points will be safe to automate. But the path to get there runs through manual orchestration first -- testing, iterating, learning what works, then productionizing.

The engineer who knows how to scope an agent, design a prompt, draw the right boundaries, and keep themselves in the loop as the orchestrator -- that's the engineer who ships.

This entire content process -- from video to blog post, LinkedIn post, images, and published to Webflow -- used to take me days. Now I can crank out content in a fraction of the time. That's the compounding effect of building the system right.

Build the team. Stay in the suit. Productionize later.

Watch the full video series:

- AI Orchestration - Build -- Designing the agents, skills, and architecture

- AI Orchestration - Deploy -- Putting it all together with LinkedIn, Webflow, and image generation

- AI Orchestration - Prove -- The results: real traction from AI-generated content

Coming up next: In the build-in-public series, I'll be tackling the next frontier -- building an AI video editor. And in the code series, we'll dive deep into the anatomy of an agent.md -- what goes into one, how to structure it, and what makes the difference between an agent that works and one that fights you.

Key Takeaways

- Agents are prompts + permissions + tools + model selection -- not just prompts. The architecture choice between agents and skills maps to real system design principles (stateful services vs pure functions).

- The most valuable part of building agents is codifying tacit knowledge -- writing the prompt forces you to articulate your process, voice, and standards in ways you've never made explicit.

- Start with manual orchestration, productionize later -- use Claude Code as your orchestration layer to test and iterate the flow. Move to LangChain/CrewAI once you've locked in what works.

- Agent definitions must be iterative -- new models change behavior, so treat your

agent.mdfiles as living documents that need regular maintenance. - Expect orchestration friction -- agents forget to call each other, try to use tools directly, and get confused about abstraction layers. It works, but stay close to it.

- Two days of agent building beat weeks of hiring -- but the real win is having a repeatable, improvable system that compounds over time.